Back to February 2025 Industry Update

February 2025 Industry Update: Fuel

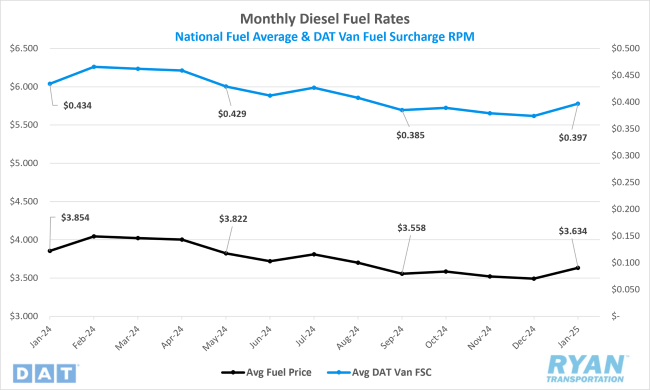

Average diesel prices rose sharply in January driven by cold weather and tightening global inventories.

Key Points

- The national average price of diesel increased in January, rising 4% MoM, or $0.14, to $3.63.

- Compared to January 2024, diesel prices were down 5.7% YoY, or $0.22 in January.

- Builds on U.S. Commercial Crude inventories outpaced draws in January by 8.2M barrels (bbls) and outperformed the consensus of 3.0M bbls for the weeks ending January 3 and January 31.

Summary

After declining in the final two months of 2024, the national average fuel price surged in January, reaching its highest level since August of the previous year. The increase in average diesel prices was driven by consistent WoW gains throughout most of the month. During the first two weeks, the benchmark diesel price, as reported by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), rose by a total of $0.10 before spiking by more than $0.11 WoW in the third week. This sharp increase marked the largest single-week rise in average diesel prices since February 12 of the previous year, when prices surged by $0.21 WoW following reports of escalating shipping attacks in the Red Sea. However, the three-week rally concluded in the final week of January, as prices declined by approximately $0.06 WoW, ultimately closing the month nearly $0.10 higher than where they began.

Despite U.S. crude inventory builds outpacing draws in January, the spread between front-month and second-month ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) futures contracts shifted from contango – where it had remained for several months – to backwardation in late December. In a contango market, the second-month settlement price is higher than the front-month price, with further increases along the futures curve reflecting storage costs and the time value of money. This structure is generally considered the norm in a balanced market. Conversely, backwardation – where front-month prices exceed those of later-dated contracts – typically signals tighter inventories and stronger demand for near-term product delivery.

Why It Matters:

The increase in fuel prices in January can be attributed to several key factors, according to commodity analysts. One significant contributor, with historical precedence, was the impact of cold weather, as diesel prices rose at a faster rate than crude oil prices throughout the month. Diesel is derived from the same distillate as No. 2 fuel oil, commonly known as heating oil, which is primarily used for residential and commercial heating. Further effects of winter weather on diesel prices were evident in the sharp rise in global liquefied natural gas (LNG) prices, which surpassed crude oil on an energy-equivalent basis – an occurrence described as “rare” in a recent Bloomberg report.

Another factor cited in January’s price surge was the imposition of new sanctions on Russian oil shipments by the outgoing Biden administration. These sanctions targeted two of Russia’s largest oil producers, as well as a broad range of shipping entities, oil service equipment firms and insurance providers. According to a report from S&P Global Commodity Insights, these sanctions were expected to reduce near-term Russian oil flows into Asia, particularly India and China. A separate Bloomberg report noted that the restrictions could significantly disrupt Russian oil exports, with initial estimates projecting a decline of 500,000 to 1 million barrels per day, though some market forecasts suggested even greater reductions.

Tighter global oil supply conditions could further pressure fuel prices, particularly as OPEC+ recently reaffirmed its planned timeline for easing production cuts and increasing output in April. In contrast, former President Trump, during his first week in office, urged the oil cartel to lower prices. While the market responded with a sharp decline in overall prices, analysts emphasized that while OPEC and the broader OPEC+ alliance set production quotas, they do not directly control oil prices.